Table of Contents

TL; DR

Healthcare interoperability is no longer a technical curiosity or an aspirational goal.

By 2026, it is a regulatory requirement, a clinical utility imperative, and a strategic differentiator for hospitals and health systems of all sizes.

Yet despite strong federal policy and decades of investment, the reality on the ground remains uneven: many hospitals struggle to routinely exchange usable electronic health information, especially in rural, independent, and small hospital settings.

This blog answers:

- Where EHR interoperability actually stands in the U.S.

- What federal standards are shaping the future

- Why barriers persist despite policy momentum

- What opportunities exist for hospitals in 2026 and beyond

EHR Interoperability in 2026 : Reality, Progress, and Gaps

The State of Adoption Across Interoperability Domains

Interoperability is often measured by whether hospitals send, receive, find, and integrate electronic patient data.

70% of non-federal acute care hospitals engaged in all four interoperability domains (send, find, receive, integrate) either routinely or sometimes in 2023. This includes any level of engagement, not necessarily full or routine exchange.

Routine use, the deeper indicator of operational interoperability, tells a fuller story:

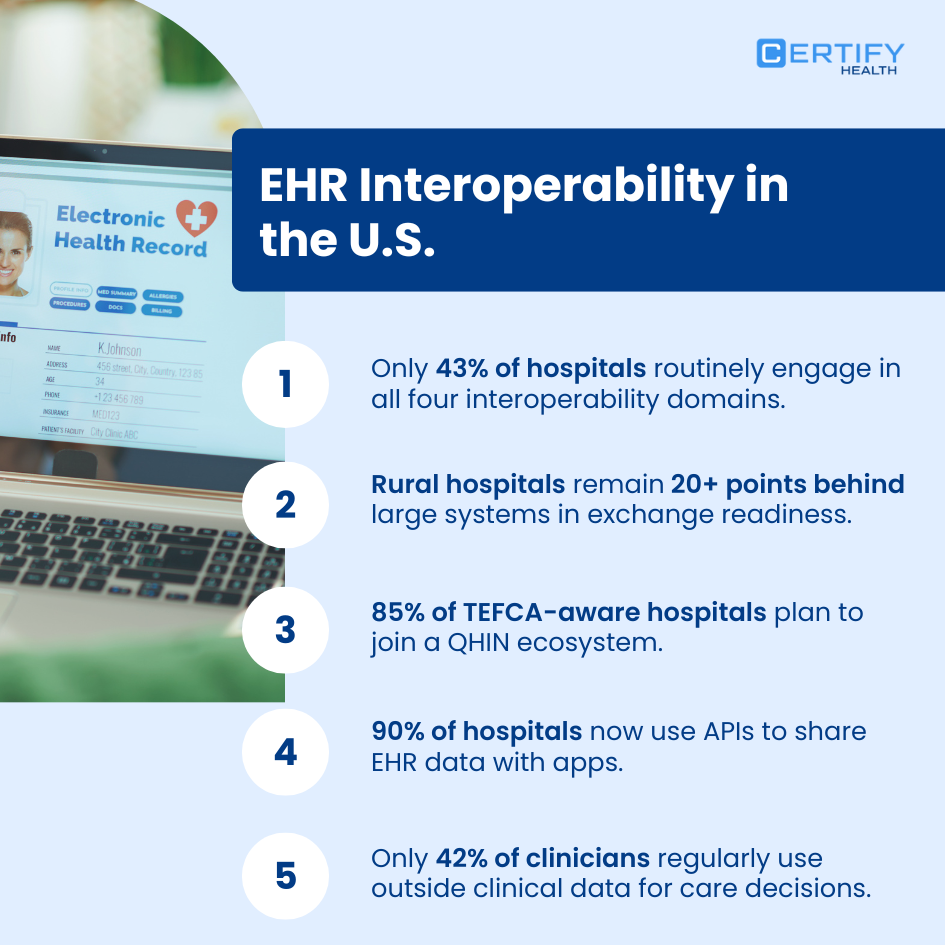

Only 43% of hospitals reported routine engagement across all four interoperability domains in 2023.

That means fewer than half reliably share usable data daily.

Routine engagement matters because every clinician decision that spans care settings depends on it.

Why Interoperability Matters for Clinical Workflow and Care Delivery

Hospitals may technically enable data exchange, but having data available is not the same as clinicians using it in care decisions.

For example, only 16–17% of hospitals reported sending summary of care records to most or all post-acute and behavioral health providers — despite interoperability progress. This highlights the gap between availability and utilization at the point of care.

Why is this gap real?

- Clinicians rarely encounter flows that are seamlessly embedded into workflows

- Some systems expose data that is too far removed from the tools clinicians actually use

- Data may be available but not trustworthy in context

This disconnect erodes the value of interoperability; not because data isn’t shared, but because it isn’t actionable.

The Federal Policy Engine Driving Healthcare Interoperability

True interoperability in the U.S. is policy-driven. Three pillars now shape how EHR systems must behave.

TEFCA: The National Interoperability Framework

TEFCA (Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement) is the nationwide architecture for health data exchange.

Policy Reality: TEFCA establishes a uniform governance and technical framework to enable nationwide exchange among Qualified Health Information Networks (QHINs) and participants.

This matters because health systems can no longer rely solely on local point-to-point exchange; standardized, governed exchange is now the federal direction.

USCDI: Core Dataset Standard

USCDI (U.S. Core Data for Interoperability) defines the data elements that must be shared. It is a uniform vocabulary for clinical data. Federal rules require USCDI to be supported for certified EHRs.

This removes ambiguity and ensures what is exchanged is interpretable by all parties.

FHIR API: The Protocol of Exchange

FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources) is the technical mechanism for exchange, defined by HL7 and widely adopted across apps and EHRs.

FHIR APIs allow systems to exchange discrete clinical data in real time rather than entire documents.

Policy Anchors: The 21st Century Cures Act

The 21st Century Cures Act and its implementing rules require EHRs to support standardized APIs and prohibit information blocking. This is a fundamental legal underpinning of interoperability.

The result is a health IT ecosystem where:

- APIs must be available

- Certified EHR technology must support interoperable data standards

- Providers cannot impede exchange without justification

These rules shift interoperability from optional to statutory compliance.

Real-World Gaps and Persistent Barriers

1. Smaller and Resource-Limited Hospitals Lag

Lower-resourced hospitals (small, rural, critical access, and independent) have lower rates of routine interoperability.

This means these providers may not reliably exchange critical patient data, exacerbating care inequity.

2. Summary of Care Exchange Remains Limited

Even hospitals that engage in interoperability across the four core domains only share summary of care records with most external providers at low rates, especially long-term care and behavioral health partners.

3. Access vs Use Gap

Clinicians report access more frequently than use. Only 42% often act on external clinical information received electronically.

This is not an API problem alone; it is a workflow integration issue.

The Role of APIs and FHIR Adoption

APIs are the gateway to interoperable functionality for clinicians and patients.

In 2022, about two-thirds of non-federal acute care hospitals used a standards-based API (largely FHIR) to enable patient access to data through apps, with growth year over year.

Key takeaways:

- Standards-based APIs are now mainstream among hospitals

- Patients increasingly access their data through apps

- Real interoperability depends on broad FHIR implementation

However, mixed API use across hospital types and systems remains a barrier, especially for non-FHIR or proprietary exchanges.

Strategic Interoperability Levers for 2026

Routinely interoperable hospitals reported markedly higher clinical data use at point of care (70%) compared to sometimes or non-interoperable hospitals, tying interoperability to usable clinical insights.

Hospitals that want to lead in interoperability must think beyond technical compliance and embrace value realization. Here are the key strategic levers:

1. Raise the Bar from Sometimes to Routine Exchange

Routine interoperability across all four domains increases not just data sharing but clinical usefulness. Hospitals should evaluate:

- Workflow pathways where data must be available real time

- Clinical contexts where external information changes care decisions

Measure success by routine engagement, not merely connectivity.

2. Expand TEFCA Participation

TEFCA participation transitions local interoperability into a national network model. Being connected to QHINs reduces interoperability islands and improves consistency of exchange.

3. Standardize on USCDI and FHIR for Semantic Clarity

True interoperability needs shared meaning, not just pipes. USCDI and FHIR ensure data fields are understood and actionable.

- Train care teams on how data is structured

- Use FHIR profiles that map clearly to clinical workflows

4. Embed External Data into Clinical Workflow

Having data is not enough if clinicians can’t use it efficiently:

- Integrate external data into EHR views that clinicians trust

- Enable decision support alerts from interoperable data

- Provide training that turns data into action

5. Address the Equity Divide

Policy success must be measured by whether all hospitals (including rural and small independent ones) can participate routinely in interoperability.

This requires intentional investment in:

- Technical capacity

- Vendor negotiation strategies

- Governance frameworks tailored to smaller organizations

Key Performance Metrics for Evaluating Interoperability Progress

| Metric | Why It Matters |

|---|---|

| Routine engagement (4 domains) | ONC benchmark for true interoperability maturity across send, receive, find, and integrate workflows. |

| Clinician use of external data | Measures whether exchanged data is actually used in care decisions at the point of care. |

| FHIR API deployment | Indicates compliance with federal standards and readiness for scalable, app-based data exchange. |

| Rural/independent hospital interoperability | Tracks equity gaps and identifies under-resourced settings at risk of lagging behind. |

A 2026 Interoperability Roadmap for Hospitals and Health Systems

0–12 Months: Baseline and Engagement

- Measure current interoperability across domains

- Join TEFCA/QHIN participation

- Assess FHIR API maturity

- Evaluate clinician usage rates

12–24 Months: Operational Integration

- Standardize USCDI conformant data flows

- Design clinician-centric data views

- Automate external information display within workflows

24–36 Months: Analytics and Population Health

- Use interoperable data for care coordination analytics

- Build predictive and population health dashboards

- Demonstrate impact on outcomes and efficiency

Conclusion

By 2026, EHR interoperability in the U.S. is no longer constrained by a lack of federal standards. TEFCA is live, QHINs are exchanging data, HL7 FHIR APIs are broadly deployed, and USCDI has defined the baseline for semantic consistency. Yet ONC data continues to show a persistent gap between technical capability and real-world clinical use, especially in rural, independent, and small hospitals.

The differentiator over the next three years will be execution. Health systems that translate interoperability into routine workflows, trusted patient identification, and clinician-ready data will see measurable gains in care coordination, decision support, and operational resilience. Those that do not risk higher clinician burden, fragmented patient records, and underutilized federal infrastructure.

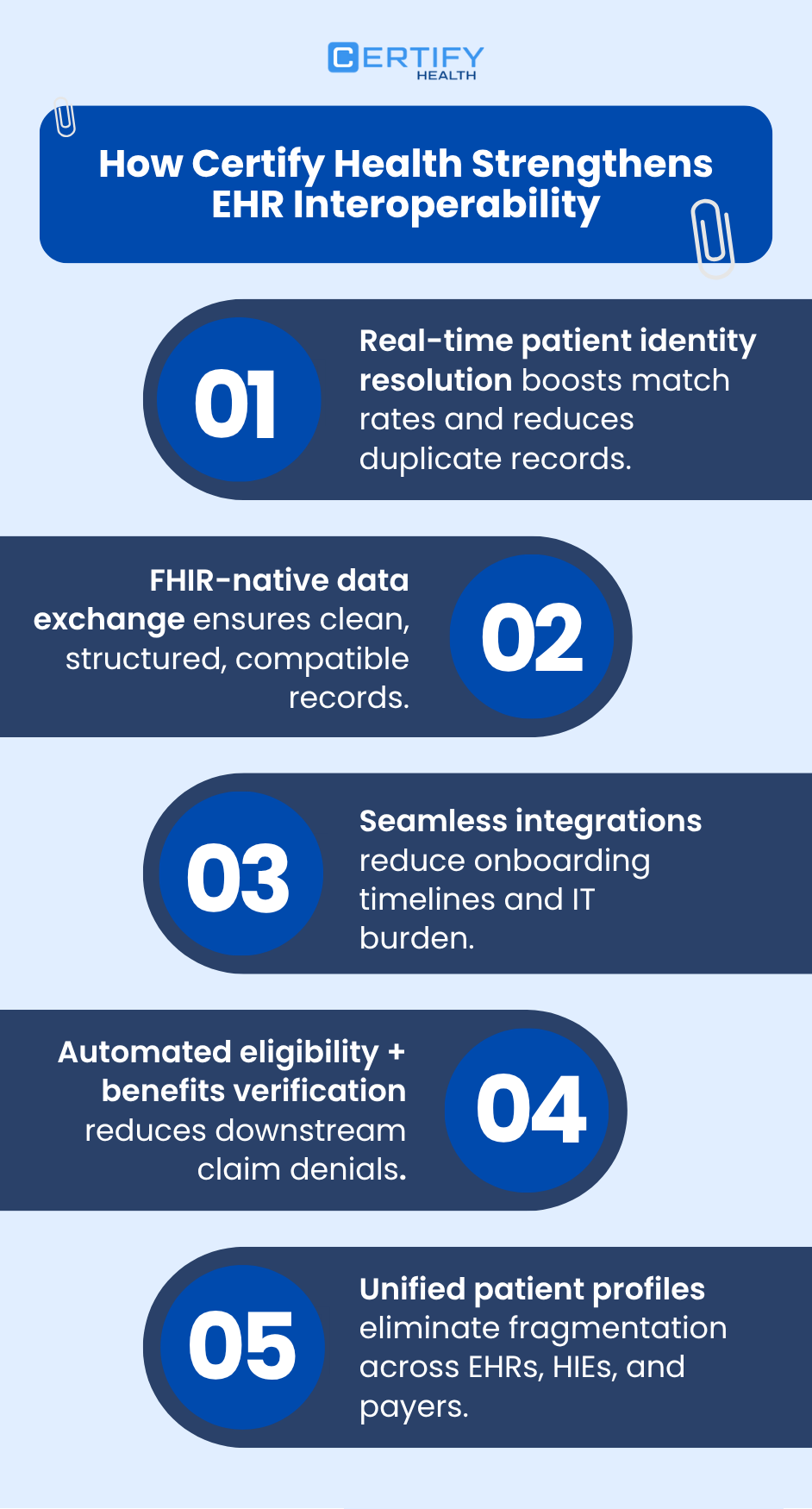

This is where CERTIFY Health stands apart.

CERTIFY Health focuses on one of the most under-addressed interoperability failure points: accurate, scalable patient identification across fragmented systems. By strengthening identity resolution at the front of data exchange, CERTIFY Health enables cleaner interoperability downstream, higher data usability at the point of care, and greater trust across networks participating in TEFCA and FHIR-based exchange. For hospitals navigating technical debt, limited resources, or cross-network data fragmentation, this foundation is critical.

For healthcare leaders preparing their 2026 interoperability strategy, the path forward is clear: prioritize standards-based exchange, invest in governance and workflow integration, and ensure patient identity is resolved before data ever reaches clinicians.

To learn how CERTIFY Health supports interoperable, identity-first exchange aligned with federal standards, visit www.certifyhealth.com or request a demo to assess readiness for TEFCA, FHIR, and USCDI-driven interoperability.

The infrastructure is finally in place. The advantage now goes to organizations that implement it correctly.